Good morning,

Remember back in April when I sent you my recipe for yuba-vegetable lasagna in “Getting to Know Yuba (Part 1/2)”? Well, I’m finally ready to share that elusive Part 2/2. (Quick reminder: yuba is the protein- and fat-rich skin that forms on the top of heated soymilk. But much more on that in a minute.)

I sought the wisdom of nine experts (they’re listed after the story below) who generously took the time to answer my questions about yuba via phone and email. Among them are award-winning cookbook authors, chefs, and yuba producers.

There are many varieties of yuba and countless dishes, both traditional and contemporary, in which to use them. I hope you enjoy the deep-dive that follows.

(Unrelated) Recommendations:

See John Proctor Is the Villain (play) ASAP.

See Audra McDonald in Gypsy (musical) before it closes on August 17.

And a much cheaper option: listen to “The Elixir of Life” episode of Radiolab.

Talk to you soon.

Brian

*Formal Assignment P.S. is for paid subscribers. It’s just $6 a month—or even less for an annual subscription.

Getting to Know Yuba: Part II

Note: For simplicity’s sake, though it goes by many names outside of Japan, I’ll refer to the subject of this story as yuba throughout.

In a cozy restaurant in Kyoto, steam rises from the fresh soymilk (two ingredients: water, soybeans) in a dinner-plate-sized hotpot at the center of your table. Within a minute or two, aided by the cold, steady breeze from the air conditioner above, a thin layer of tender, delicately chewy skin has formed on the surface of the creamy liquid. With chopsticks, you gently lift it like a wet, wrinkled velvet cloth from the hotpot. You dip it in soy sauce or citrusy ponzu and bring it to your mouth, still warm, dripping lightly.1

Jenny Yang, the owner of Phoenix Bean in Chicago, recalls this experience when she harvests a fresh sheet of warm yuba (the Japanese name for the protein- and fat-rich soymilk skin) from the table of steaming trays in her company’s production facility, before it has a chance to make its way to the “laundry line” of hanging sheets.

My own first tastes of yuba, only months ago, were less traditional and more adulterated, taking the form of a yuba-and-vegetable lasagna and a “yuba milanese” I made, and a Philly cheesesteak-reminiscent sandwich at Superiority Burger in New York’s East Village.

I’d come across yuba by chance while pondering grain-free alternatives to lasagna noodles and had been pleasantly surprised to find that a natural-foods store in my rural area carried Hodo, the only nationally distributed packaged brand of it. After the success of my Italian-inspired experiments, I was desperately curious to see how the sausage was made, so I ordered dried soybeans, made my own soymilk, and harvested a taste of the skin that formed atop it in the process: warm, slick; nutty soy flavor with the texture of a fatty prosciutto slice.

The soymilk skin that would eventually go by many names2 (among them, the Japanese “yuba,” and the Mandarin “doufupi,” meaning “tofu skin” — though yuba is not actually tofu, as it requires no coagulant) was first mentioned in writing towards the end of the sixteenth century in both Japanese and Chinese texts, according to the California-based Soyinfo Center. By that time, it was already appreciated, at least by Li Shizen, the writer of the Chinese text, as “a delicious food ingredient.”3

Variations in harvesting and preservation methods, the latter namely by drying, would give yuba (or its local counterpart) a range of textures and culinary uses across Asia.

Naoko Takei Moore, owner of TOIRO Kitchen & Supply in Los Angeles and author of A Very Asian Guide to Japanese Food wrote in an email, “Dried yuba is often used in simmered dishes, hot pots, or soups.” (Minh Tsai, Hodo’s founder, described similar preparations from his childhood in Vietnam.) In her book The Vegan Chinese Kitchen, Hannah Che writes of “a remarkable creation of semi-dried tofu skin”: the “vegetarian roast goose” that is one of Jiangnan Province’s “classic dishes.” Her description of the mock-goose dish is mouthwatering: “The delicate sheets are layered, filled with mushrooms and vegetables, rolled into a packet, steamed, and then fried to a shatteringly crisp exterior, in imitation of crispy goose skin…” Clarissa Wei, author of Made in Taiwan, described in an email a traditional Taiwanese preparation: tofu skin “braised with napa cabbage in a shrimp-brined broth with wood ear and shiitake mushrooms.”

At least some of the creative energy historically applied to tofu skin was rooted in the ingredient’s potential to accommodate religious dietary restrictions while approximating the nutrients and satisfying texture of absent meat. According to Che, Jiangnan (the historical province that produced the goose-like dish) was “Home to one of the oldest and largest Buddhist populations in China,” making it “a hub of vegetarian cuisines during the Song dynasty” (960-1279 AD)4.

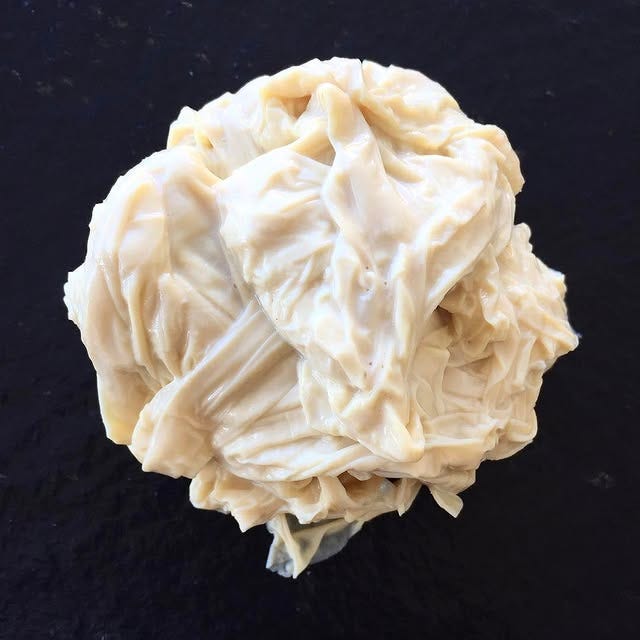

Fresh yuba, which ranges in consistency from the soft and scoopable – like ricotta or burrata – to the meatily chewy – like al dente pappardelle – is a specialty of Japan, especially Kyoto, and Taiwan. Tsai visited Japan “almost a decade ago” to learn all he could about the “dying art” of yuba-making. “There are families that have been around for 10 to 15 generations in Kyoto making tiny productions” of yuba. “And each family or yuba shop specializes in a specific type.”

Tomoko Imade Dyen, a self-described “Japanese culinary curator” from Tokyo who lives in Los Angeles, lamented that “many traditions are disappearing” in her native city; when she visits, she now finds she has to “go to grocery stores to buy fresh yuba in plastic packaging” in light of the dwindling presence of yuba shops. And yet, fresh yuba persists in some areas. Mark Okuda, chef-owner of The Brothers Sushi in Los Angeles, recently visited Tochigi prefecture, “about an hour and a half north of Tokyo by train,” and encountered countless varieties of yuba in restaurants, convenience stores, and gift shops.

In a world where speed, automation, and cost-effectiveness often prevail over much else, yuba is a tough sell. Tsai puts it in plain terms: although it’s not very difficult to make, “it’s very time-consuming and space-consuming, so it’s not a profitable business to make and sell yuba.” There’s no known way to reduce the time required for each individual layer of skin to develop, and each tray of steaming soymilk requires a significant amount of lateral real estate (generally about a half-sheet-pan’s worth). Then the harvested sheets need somewhere to hang-dry, at least partially. If completely dried, yuba has a virtually unlimited shelf-life, but fresh yuba survives only a few days. (No wonder, then, that the latter is seen more often at formal dinners, restaurants, or hot spring hotels -- “ryokan” -- than at home.)

Harvesting is done the old-fashioned way at both Hodo and Pheonix Bean. Yang described a table covered with twenty sheet-pan-sized heated trays around which an employee rotates, harvesting from each tray and hanging the yuba before moving on to the next. After drip-drying, the sheets are folded. (Tsai has seen equipment in Japan that automates the harvesting process wherein a mechanized stick lifts the skin from a long trough of soymilk and very slowly rolls it – but his investment in such massive, expensive, Japanese-sourced equipment is a long way off. ) Pheonix Bean vacuum-seals the folded yuba and sells some fresh, some frozen. Yang sent me some sheets of frozen yuba and when I finally thawed them in cold water months later, they unfolded flawlessly. Hodo introduced a steam-pasteurization step to the packaging process in order to extend their fresh yuba’s refrigerated shelf-life to a month or longer, making their product’s nationwide distribution possible.

As a minimally processed protein-rich meat alternative (“It’s the closest thing there is to a non-processed mock meat,” said Tsai), yuba has gained a presence on the radar of US-based chefs who have given plant-based menu options, if not entire menus, more attention in recent years. Yang sells mostly to restaurants; “They put it in tacos and hamburgers,” she said, as well as in more traditional dishes such as okonomiyaki (savory pancakes). Though either product might end up sandwiched inside a hamburger bun, the meditative process of making two-ingredients yuba is the furthest thing from the process that spawns lab-grown meat alternatives.

Tsai first noticed that yuba was getting some attention from chefs outside of Asia when he read Daniel Patterson’s 2006 piece in The New York Times, essentially a love letter to the soy product that became an “infatuation” once he tasted it in Kyoto. With the right seasoning and preparation, yuba can mimic the flavorful crunchy-chewy textures of poultry skin or bacon. Nancy Singleton Hachisu, author of Japan: The Cookbook, prefers the ultra-soft variety of yuba, for its “clean taste” and mildly nutty soybean flavor, to the burrata to which it’s often compared. Others cut firmer yuba in thin strips and use it as one would al dente pasta, whether sauced or in chicken noodle soup.

Yuba is clearly versatile and has the potential to be used in endless creative ways; as Tsai said of the ingredient’s presence in Western dining, “it’s still very early days,” and we have a lot to look forward to in terms of its exploration. New frontiers aside, there’s plenty of simple pleasure to be derived from watching a skin form atop a pot of steaming homemade soymilk, gently lifting it with chopsticks and bringing the warm, draped and dripping clothlike membrane towards your watering mouth.

The Experts

I’m grateful to the following people who shared their yuba expertise with me via email or phone for this piece.

is the author of Made in Taiwan. She was born and raised in Los Angeles and now lives in the hills of Taipei.

Jenny Yang, originally from Taiwan, owns Pheonix Bean in Chicago.

Judy Leung is co-author, along with her two daughters and husband, of The Woks of Life: Recipes to Know and Love from a Chinese American Family.

Mark Okuda is the chef-owner of The Brothers Sushi in Woodland Hills, California. He’s procured yuba from Meiji Tofu in Gardena and most enjoyed serving it cold, with sea urchin and dashi.

Minh Tsai, a self-described “yuba evangelist,” is the founder of Hodo Foods in Oakland.

Nancy Singleton Hachisu is the author of Japan: The Cookbook. She has lived in the Japanese countryside since 1988.

Naoko Takei Moore is the author of A Very Asian Guide to Japanese Food and owner of TOIRO Kitchen & Supply in Los Angeles.

Rie McClenny is a video creator and the author of Make It Japanese. She was born and raised in Hiroshima and now lives in Los Angeles.

Tomoko Imade Dyen is a “Japanese culinary curator” originally from Tokyo. She lives in Los Angeles.

Though I didn’t have a chance to speak with her,

’s book, The Vegan Chinese Kitchen, was a valuable source of information and very tempting recipes.YUBA: WHERE TO FIND AND HOW TO USE

Find it:

Where to find Hodo Foods products across the US (be sure to ask stores specifically if they stock Hodo’s yuba)

In Chicago (or via mail): Phoenix Bean

Ask local soymilk or tofu producers if they sell yuba

Use it (recommendations from the experts):

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Formal Assignment to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.